Live to die another day

Introducing the gene model and the results from a large number of simulations

For previous articles checkout the experiment list or for a complete overview of the project go to GitHub repository.

20,000 simulations under the CPU

A Dooder is an artificial agent designed to learn and act within a simulated environment while maximizing its energy consumption and lifespan. This experiment will take a large group of simulations and compare the results.

In a previous article, I discussed a simulation involving a single Dooder spanning one hundred cycles. This experiment will run the same simulation, just 20,000 times. Additionally, I aim to analyze the factors contributing to the divergence between Dooders that accomplish the objective and those that fail.

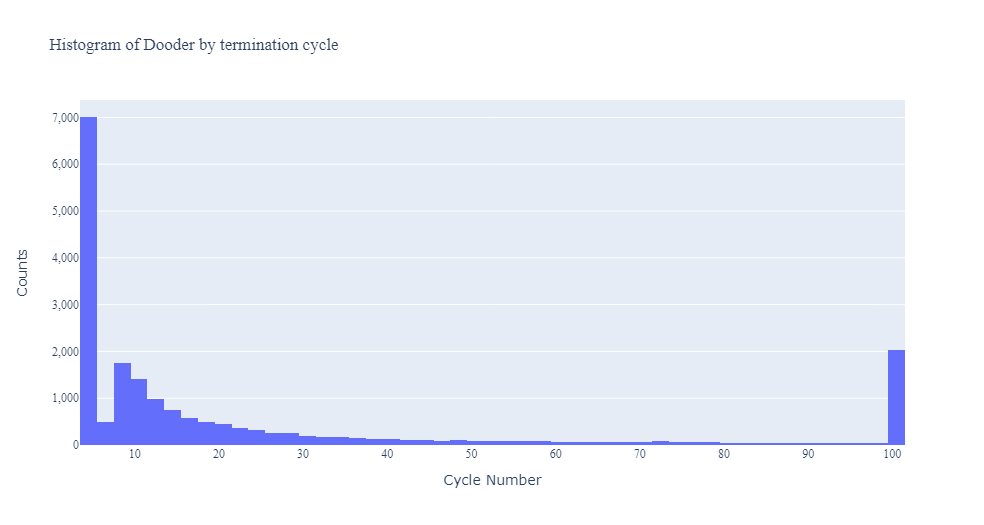

Figure-1 is a histogram of the 20,000 Dooders showing the distribution of ages at termination. 10% of the Dooders made it to the end of the simulation while 35% didn’t make it past the first 5 cycles. But before we go deeper into the results, I will introduce the project’s gene model.

Gene machines

“They have come a long way, those replicators. Now they go by the name of genes, and we are their survival machines.” - Richard Dawkins (The Selfish Gene)

A gene is a repository of biological information capable of being activated and expressed in various ways1. Richard Dawkins described genes as employing organisms as vehicles to ensure their own replication2. Much like a baton in a relay race, passed from one runner to another, except the winners of this race are the runners still passing the baton.

The traits of these organisms are shaped by the selective pressure exerted on their genes, refining and molding their characteristics over time.

In a Dooder, a gene refers to the neural network parameters that constitute an agent's internal models3. These models play a significant role in directing the agent's actions within the simulation and determining its responses to the environment.

Investigating the metaphorical gene pool from a group of Dooders is challenging; however, one approach to simplify the analysis is to generate an embedding.

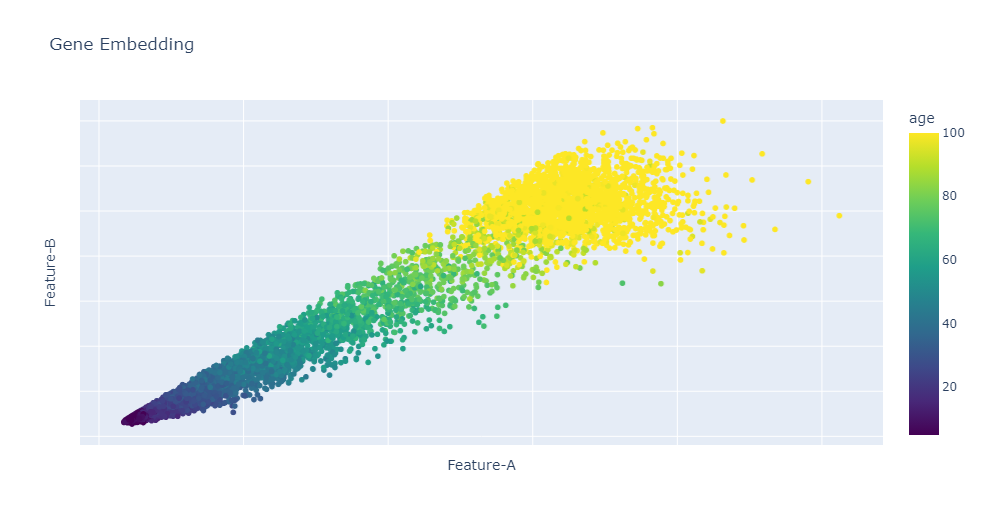

An embedding is a powerful machine learning technique used to transform high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional vector space4. Typically, this transformation involves capturing and representing essential patterns and features present in the data. In the context at hand, the embedding process condenses 1,042 gene values taken from the energy-seeking model into three distinct feature values: Feature-A, Feature-B, and Feature-C.

The embedding facilitates easier analysis and understanding of the genetic makeup of the Dooders over time. However, it is not always clear what these features represent.

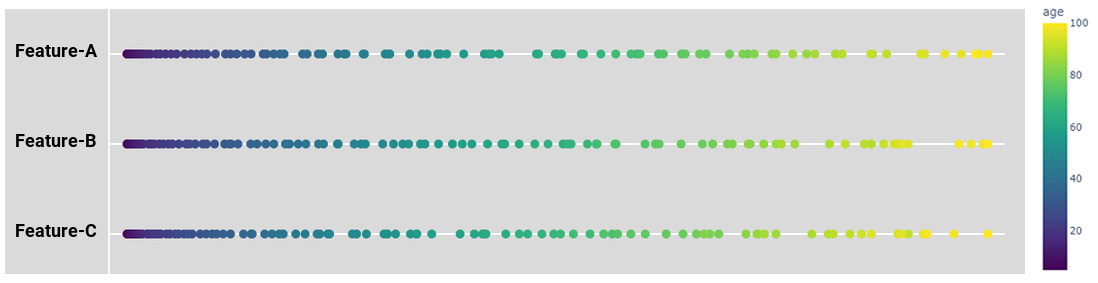

Below are a few examples to visualize the features from the energy-seeking gene. You’ll notice a consistent pattern throughout each image. When we get to a point of examining simulations with thousands of cycles, there are some incredible patterns that I’m not sure how to interpret.

One-dimensional

The chart depicted in Figure-2 progresses from left to right showing the change in the energy-seeking gene colored by a Dooder’s age in the simulation. There are periods of greater change, especially after the initial cycles.

Two-dimensional

Three-dimensional

Energy-seeking behavior

“No aspect of life can function without energy” - Geoffrey West (Scale)

The simulation requires a fundamental driving force, a mechanism that fosters continuous growth and complexity. This underlying force serves as a persistent and captivating motivation, providing purpose to the agents within the simulation: to perpetually seek and utilize energy.

🔋 In this project, energy is purely conceptualized as a digital entity, without any physical properties.

Until now, my focus has been primarily on the energy-seeking model, without delving into other current or future gene models. A fundamental characteristic of intelligent life is its ability to navigate the environment and actively seek out energy sources. Movement is a capability that a Dooder must demonstrate in order to thrive.

One approach to modeling behavior is through the implementation of mechanisms that facilitate the occurrence of desired behaviors. Rather than enforcing explicit rules dictating that Dooders must consume energy, my approach is to create an open-ended system5 where the survival of Dooders is determined by their ability to proactively seek out and consume energy.

By not imposing strict rules, the open-ended system provides Dooders with the freedom to experiment, adapt, and evolve their behaviors.

Moreover, the open-ended nature of the system allows for the possibility of unexpected and emergent behaviors. Dooders may stumble upon novel ways to locate and consume energy that were not initially anticipated. This open-ended evolution6 encourages adaptive and creative approaches from the Dooders, potentially leading to a more dynamic and diverse range of behaviors when the simulation is more complex.

The gene embeddings depicted in Figures 2 to 4 represent a conceptual gene pool engaged in the pursuit of an optimal strategy to locate resources. That is a common effect of gradient descent optimization which works a lot like tuning a radio to a desired station. Moving the knob back and forth until the sound is clear and crisp.

In a future article, I will explore a gene to model a reproduction mechanism for Dooders to create new agents and propagate their genes into future generations.

Winners and losers

Why do some Dooders make it to the end of the simulation and others die early?

Mostly luck.

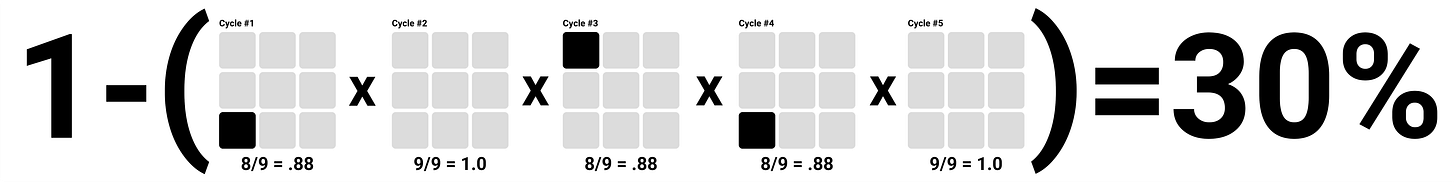

At first, the Dooders are choosing random spaces and only learn as they gain experience. Some go 5 cycles without choosing a space with energy, perishing as a result. Others are more fortunate and choose a correct space, and not because they “know” where to go to get energy. It isn’t until about 40 cycles before a Dooder can somewhat accurately identify nearby energy.

The 20,000 Dooders can be separated into 3 categories:

FailedEarly - Failed after 5 cycles

Failed - Did not make it to 100 cycles

Passed - Made it to 100 cycles

To measure how likely a Dooder was to make it past it’s initial cycles I calculated the complimentary probability of the first 5 cycles the Dooder encounters from the number of spaces in the agent’s perspective that has energy. Calling it “Starting Success Probability”.

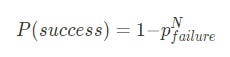

Where p is the probability of failure calculated for each successive N cycles. For example, taking a random Dooder from the 20,000 and looking at the number of spaces with energy during its first cycle we can calculate the probability it will select a space with energy, i.e. success. The image below shows 8 spaces have no energy meaning there is a 11% chance that the Dooder will select a space with energy.

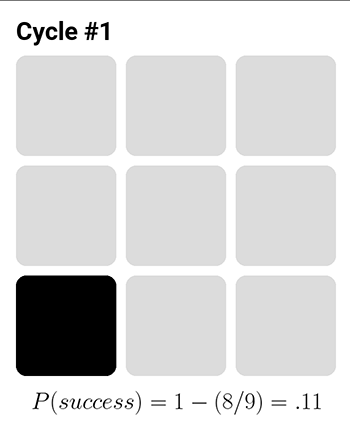

By applying that same logic to the first five cycles, as depicted in the accompanying image, there was a 30% probability for this Dooder to successfully navigate through the initial five cycles if the selection process was random. In reality, it did not select a space with energy and was terminated.

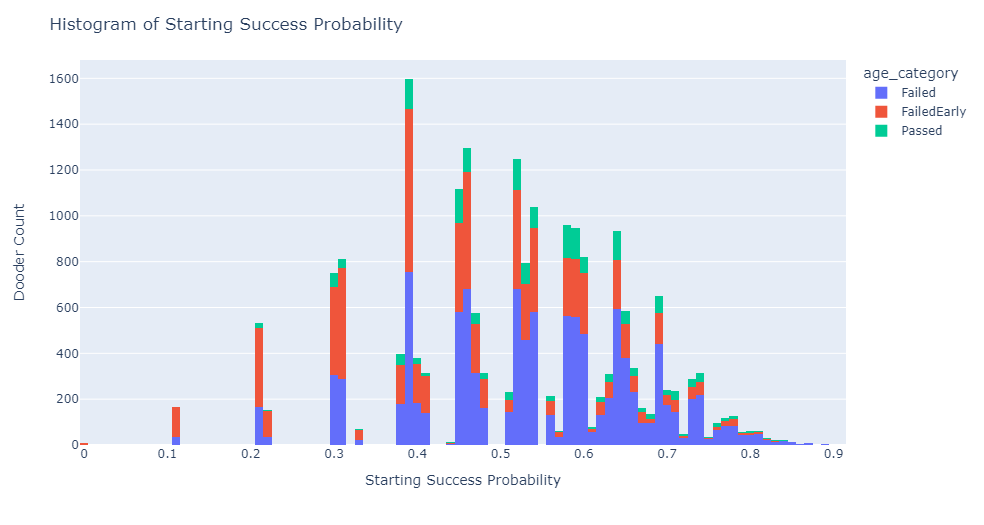

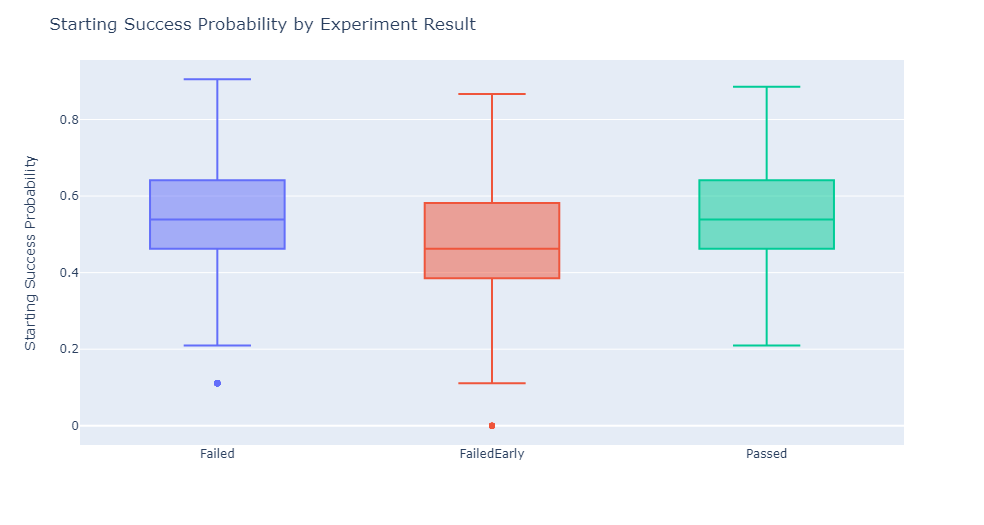

Figure-5 and Figure-6 show the probability of success for all 20,000 Dooders grouped by the experiment categories (FailedEarly, Failed, Passed):

Stuck in a rut

If a Dooder manages to surpass the initial 5 cycles with a stroke of luck, it can accumulate sufficient experience to better discern the presence of energy within its surroundings. As depicted in Figure-7, with each successive cycle, the average accuracy gradually increases.

One interesting phenomenon observed in some of the Dooders was their tendency to become "stuck" in a repetitive movement pattern for multiple cycles, regardless of the actual circumstances they encountered. This behavior can likely be attributed to a limitation in the simple neural network architecture I’m using.

Out of the Dooders that managed to persist beyond the initial 5 cycles, 87% of them fell into the trap of continuously choosing the same movement direction. The majority remained trapped in this state until they were terminated, while a few managed to break free at some point.

To illustrate this behavior, the animation below shows a specific Dooder that became stuck in a repetitive movement pattern after 42 cycles until it expired due to starvation.

Amazingly, among the Dooders that successfully completed the simulation (Passed), 92% of them experienced moments of being stuck, but the vast majority (82%) eventually found a way to break free from this repetitive cycle. It appears that overcoming this stagnation was a crucial factor in their overall success. As I mentioned earlier, it is highly likely that this behavior stems from the limitations of the neural network architecture. I will closely monitor this behavior in future experiments to see if it continues and dive deeper if necessary.

What’s next?

This experiment provided valuable insights into Dooder behavior based on the current code and simulation complexity. However, to ensure thorough testing and optimization of the neural network infrastructure, I plan to transition from the simple neural network library to a more widely-used and optimized framework such as PyTorch or Mojo.

In the near future, I have outlined several experiments that I plan to pursue:

Reproduction model

Develop a mechanism that enables the combination of gene-models from two Dooders, simulating the process of reproduction and introducing genetic variation into the population.

Competition

To further enhance the simulation, I will introduce a larger population of Dooders, where they must now compete with each other for limited energy resources.

Complex energy

In order to enable Dooders to perform more complex actions, I plan to introduce a variety of energy types.

Footnotes

“The Gene: An Intimate History” by Siddhartha Mukherjee

“The Selfish Gene” by Richard Dawkins

“We must not forget that the internal model must be embodied in a system with a mechanical design that allows the agent to benefit from the accuracy of the model.” - The Romance of Reality by Bobby Azarian

https://www.featureform.com/post/the-definitive-guide-to-embeddings

https://www.oreilly.com/radar/open-endedness-the-last-grand-challenge-youve-never-heard-of/

https://hugocisneros.com/notes/open_ended_evolution/